Content

By E. Wesley F. Peterson

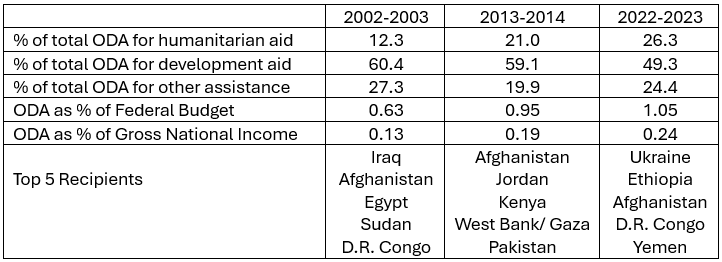

According to a recent poll, U.S. adults think on average that about 26 percent of the federal government’s budget goes to foreign aid with some believing that more than half is put to that use (Tierney 2025). Public opinion surveys have returned similar results for many years with most respondents seeming to believe that this is far too generous often suggesting that something on the order of 5 percent of federal spending would be more appropriate. In fact, until recent efforts to eliminate foreign aid altogether, the actual amounts spent have represented one percent or less of the federal budget (see Table 2). The elimination of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and severe reductions in the spending of humanitarian and development funds appropriated by the U.S. Congress are of questionable legality and with unresolved legal challenges still in the works it is not clear precisely how the U.S. role in foreign assistance will evolve in the future. In that context, some factual information about foreign aid may be of use.

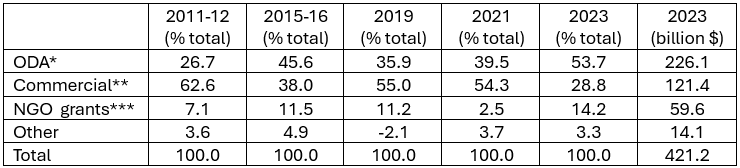

In all countries, capital investments are a key element in promoting economic growth and development. In low- and middle-income (LMI) countries, capital is often scarce, making it difficult to procure needed investments. Foreign aid—low-interest loans and grants from governments in high-income countries to governments, civil society organizations, and international agencies in LMI countries—is one source of investment financing (see Table 1). In the terminology of international development organizations, foreign aid is known as “official development assistance (ODA).” Other sources of investment capital include direct private-sector investments and loans at market interest rates and private philanthropy through non-government organizations (NGOs). In 2023, the total amount transferred from high-income countries to LMI countries was about $421 billion (0.4% of a world economy of more than $106 trillion), with ODA accounting for 53.7% of the total, commercial investments for 28.8%, and private philanthropy for 14.2%. These proportions have varied considerably over time, as shown in Table 1. There is one other important source of funds flowing to LMI countries: money sent to their families by immigrant workers in high-income countries. In 2023, these “remittances” amounted to $647 billion compared to the total financial flows of $421 billion in that year (Ratha et al. 2025).

Table 1. Financial Flows from High-Income Countries to Low- and Middle-Income Countries.

Source: OECD (2025)

*Official Development Assistance; **Private sector investments and loans at market rates; ***Non-Government Organizations (philanthropy).

In addition to the financial flows shown in Table 2, the United States provided about $8 billion in military and security assistance in 2023, not including military sales or most of the military aid sent to Ukraine (Desilver 2025). Development aid includes programs targeting education, health, water, and sanitation, among others, while humanitarian aid consists of emergency responses, food aid, reconstruction, and disaster prevention (Ingram 2024). The United States has historically provided the greatest amount of ODA among the high-income countries, but, because the U.S. economy is so large, these contributions amount to only about a fifth of one percent of gross national income (GNI). In comparison, Norway’s 2023 ODA represented 1.09% of its GNI, with Sweden at 0.93%, Germany at 0.82%, Denmark at 0.73%, and the average for all high-income countries at 0.44% (OECD 2025).

Table 2. US Official Development Assistance: Uses, Percentage of Federal Budget and US Economy, Top Recipients.

Source: OECD (2025)

Some experts on international relations are critical of foreign aid. Moyo (2010) has argued that foreign aid has actually been detrimental to development in Africa, and Easterly (2006) contends that foreign aid has become a self-replicating industry more interested in maintaining the foreign aid system than in promoting development. On the other hand, there have clearly been some notable successes, particularly in the areas of health and disease eradication. Smallpox, a disease that once afflicted millions of people, was eradicated in 1977 as a result of a global vaccination campaign by the World Health Organization (WHO), USAID, and other international agencies, and polio has been eliminated in all but two countries. Other notable successes include the Green Revolution, which significantly reduced extreme food insecurity in Asia, and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), credited with saving 25 million lives from HIV/AIDS (Ingram 2024). The United States has also contributed about $4 billion annually in food assistance to conflict zones in which hunger and starvation are acute through the Food for Progress program. The food and agricultural goods distributed through this program are purchased from U.S. farmers and agribusiness firms, bolstering the prices they receive for these goods. In fact, a significant amount of U.S. foreign aid is actually spent in the United States for medicinal goods, food, equipment, and salaries for U.S. citizens employed as technical consultants and project managers (Ingram 2024).

It should also be noted that considerable progress has been made in improving the effectiveness of foreign assistance. Behavioral economists such as Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo (2019), who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2019, have developed economic experiments to test which interventions are the most effective in reducing poverty and generating sustainable development. Beyond these tangible impacts, U.S. foreign aid has contributed importantly to the nation’s “soft power.” Gettleman (2025) points to Kenya as a reliable U.S. ally as a result, in part, of generous foreign aid provided to that country. Many foreign policy analysts believe that U.S. cessation of foreign aid efforts will result in an expansion of the global influence of China and Russia at the expense of the United States (Ingram 2024, Desilver 2025). More importantly, the interruption of food aid and other humanitarian programs will lead to estimated deaths of more than 91,000 adults and 190,000 children over the coming year, deaths that would not occur if the U.S. foreign aid programs were not suspended (Nichols and Moakley 2025).

E. Wesley F. Peterson

Department of Agricultural Economics

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Sources

Banerjee, Abhijit and Esther Duflo (2019). Good Economics for Hard Times, New York: Public Affairs.

Desilver, Drew (2025). “What the Data Says about U.S. Foreign Aid,” Pew Research Center, available at: What the data says about US foreign aid | Pew Research Center

Easterly, William (2006). The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good, New York: Penguin.

Gettleman, Jeffrey (2025). “The Influence of Foreign Aid,” New York Times (February 21).

Ingram, George (2024). “What is US Foreign Assistance?” Brookings, available at: What is US foreign assistance?

Moyo, Dambisa (2010). Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Nichols, Brooke and Eric Moakley (2025). “Deaths Caused by Funding Discontinuation- All Tracked Programs,” impactcounter.com available at: Impact Dashboard - Impact Counter | Impact Counter

OECD (2025). “Finance for Sustainable Development,” Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), available at: Finance for sustainable development | OECD

Ratha, Dilip, Sonia Plaza, and Eung Ju Kim (2024). “In 2024, Remittance Flows to Low- and Middle-Income Countries are expected to reach $685 Billion, Larger than FDI and ODA Combined,” World Bank Blogs, available at: In 2024, remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries are expected to reach $685 billion, larger than FDI and ODA combined

Tierney, Abigail (2025). “Share of the Federal Budget Spent on Foreign Aid, According to U.S. Adults,” Statistica, available at: https://www.statistica.com/statistics/1610869/guesses-on-how-much-federal-budget-is-foreign-aid