Content

Nov 5, 2025

By E. Wesley F. Peterson

Thomas Malthus (1798/2004) famously argued that population would always tend to grow more rapidly than food production, with the result that average incomes would be driven down to a subsistence level just adequate for the population to reproduce itself. His analysis also implied that the total population could only grow as fast as the very slow growth in food supplies. This characterization was essentially correct for the centuries that preceded the publication of his essay in 1798 but was seriously off the mark for the centuries that followed. World population in 1800 was around a billion people compared with over 8 billion today, while current real global per capita income is fifteen times that of 1800. During the 19th Century, food production increased more rapidly than population as a result of increasing land availability as new areas were settled, while during the 20th Century, growth in agricultural output outstripped that of population because of scientific research and technological innovation that gave rise to increased yields (Dimitri et al. 2005).

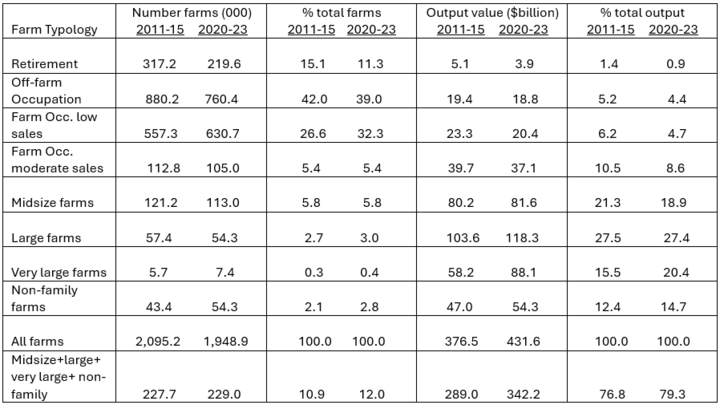

In 1870, there were about 2.66 million farms in the United States farming a total of 407.7 million acres for an average farm size of 153 acres (NASS 2025). In 1935, the number of farms peaked at 6.81 million working over a billion acres with an average farm size of 155 acres (Keller and Kassel 2025). As shown in Table 1, the average number of farms for the period 2020-23 fell below two million (1.88 million in 2024), down slightly from the average for the period 2011-15. The decline in farm numbers since 1935 has been driven primarily by technological innovations that have tripled total factor productivity in agriculture (Njuki et al. 2025). While output tripled between 1948 and 2021, land and labor inputs fell by 28% and 76% respectively. The amount of land on farms has declined very little since 1935, so average farm size has risen, reaching 466 acres in 2024 (Lim et al. 2024). Along with changes in farm numbers, the percentage of the total population living in rural areas has fallen from 40% in 1900 to 16% today, and the proportion of the U.S. labor force working in agriculture has declined from 41% in 1900 to less than 2% (Dimitri et al. 2005, Lusk 2016).

USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) uses a “farm typology” to describe the structure of U.S. agriculture. This system divides farms into small (gross cash farm income—GCFI—of less than $350,000), midsize (GCFI between $350,000 and $999,999), and large farms (GCFI over $1,000,000). Small farms are divided into retirement farms in which the principal operator is retired, off-farm occupation farms in which the primary occupation of the operator is not farming, and farms that declare farming as the principal occupation, divided into those with GCFI of less than $150,000 and those with GCFI between $150,000 and $349,999. Large farms are divided into those with GCFI of $1,000,000 to $4,999,999 and those with GCFI greater than $5 million (Lim et al. 2024). All of these are considered family farms defined as farms “in which the majority of the business is owned by an operator and/or any individual related by blood, marriage, or adoption,…” (Hanrahan 2024). A final category is made up of nonfamily farms, which account for only 2%-3% of all U.S. farms. It is important to note that any enterprise that sells agricultural products worth at least $1,000 is considered to be a farm. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, that definition means that large numbers of very small farms are included in the set of all farms. In fact, small farms make up about 88% of U.S. farms but account for only 21% to 23% of the value of total agricultural production. About 229,000 midsize, large, and nonfamily farms (12% of the total number of farms) produce almost 80 percent of total output (Table 1).

Table 1: Number of Farms, Value of Total Output, Percentages of Totals by Farm Typology*

Source: ERS (2025), ARMS

*Averages for the periods 2011 to 2015 and 2020 to 2023.

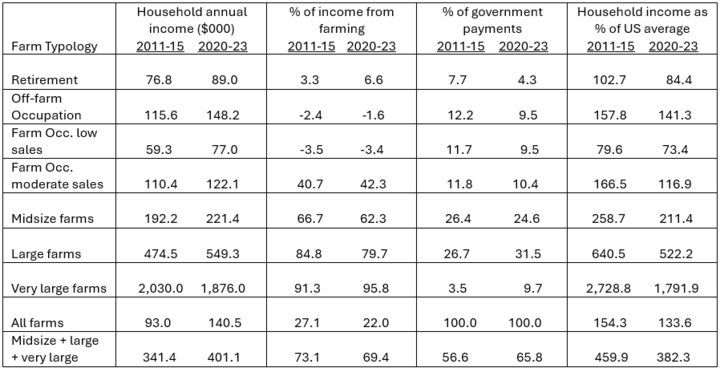

Data in Table 2 show that farm households have annual incomes above the average for non-farm households and get significant amounts of income from work off the farm. There is significant variation across the different farm types with respect to these characteristics. For example, off-farm-occupation households and farm-occupation households with low sales have both lost money on their farming activities in recent years. Despite these losses, the off-farm-occupation households have significantly higher total income than that of non-farm households. Farm households with low sales, on the other hand, have lower total household incomes than non-farm households. Retirement farms also recorded lower household income than non-farm households in recent years, but as these farm operators probably own their homes, they may not be too financially stressed. About 66% of government payments are directed at the midsize and large farms, which account for less than 10% of all family farms and have about four times the average income of non-farm households. In 2023, 21% of small family farms received government payments, mostly for participation in the Conservation Reserve Program, while 44% of midsize and large family farms received some form of government payment (Lim et al. 2024).

Table 2: Operator Household Income, percentage of income from farming, percentage of government payments received, farm household income compared to non-farm household income.*

Source: ERS (2025), ARMS

* Averages for the periods 2011 to 2015 and 2020 to 2023.

In 1962, Michael Harington claimed that there were more than a million family farms that were part of the “other America” characterized by poverty and hopelessness. While rural poverty rates are still slightly higher than urban, the gap has narrowed (Farrigan 2025), and most farm households today appear to be quite prosperous. For small farms, this is mostly due to off-farm income, while for the midsize and large farms that produce most of the nation’s food, technological innovation and productivity increases have led to greater output and household incomes well in excess of the average income of non-farm households.

Sources

Dimitri, Carolyn, Anne Effland, and Neilson Conklin (2005). “The 20th Century Transformation of U.S. Agriculture and Farm Policy,” Report No. EIB-3, USDA, Economic Research Service.

ERS (2025). “Farm Structure and Finance,” Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS), Economic Research Service, USDA available at: https://my.data.ers.usda.gov/arms/tailored-reports

Farrigan, Tracy (2025). “Rural Poverty and Well-being,” Economic Research Service, USDA, available at: https://www.ers.usda.gpve/topics/riral-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being#historic

Hanrahan, Ryan (2024). “Nearly All US Farms Are Family Farms, USDA Says,” available at: https://farmpolicynews.illinois.edu/2024/12/nearly-all-us-farms-are-family-farms-usda-says/

Harrington, Michael (1962/1997). The Other America: Poverty in the United States, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Keller, Andrew and Kathleen Kassel (2025). “Number of U.S. Farms Continue Slow Decline,” available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note/chart-detail?chartId=111304

Lim, K., J. McFadden, N. Miller, and K. Lacy (2024). “America’s Farms and Ranches at a Glance: 2024 Edition,” Report No. EIB-283, USDA, Economic Research Service.

Lusk, Jayson (2016). “The Evolution of American Agriculture,” available at: https://jaysonlusk.com/blog/2016/6/26/the-evolution-of-american-agriculure

Malthus, T. R. (1798/2004). An Essay on the Principle of Population, Oxford (U.K.): Oxford University Press.

NASS (2025). “Selected Statistics of Agriculture,” National Agricultural Statistics Service, USDA, available at: https://www.nass.usda.gov/AgCensus/archives/filews/1870c-05.pdf

Njuki, Eric, Roberto Mosheim, and Richard Nehring (2025). “Agricultural Productivity in the United States,” Economic Research Service, USDA, available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/agricultural-productivity-in-the-united-states

E. Wesley F. Peterson

Professor

Department of Agricultural Economics

University of Nebraska

epeterson1@unl.edu