Content

November 19, 2025

By Tina Barrett, Executive Director, Nebraska Farm Business, Inc.

Each year, the numbers tell a story. The 2024 data from Nebraska Farm Business, Inc. show a familiar one: tight margins, rising interest costs, and shrinking working capital. Even though fertilizer prices dropped nearly $45 per acre over 2023 for irrigated corn, other costs and weaker revenue kept the average operation under pressure. When prices and yields are out of our control, the best opportunity for 2026 is to focus on what we can manage—costs.

Why 5% Matters

It’s easy to think 5% doesn’t move the needle much. But across a full crop mix, it can make a big difference in both profitability and cash flow.

Irrigated Corn (2024 NFBI Average)

Direct expenses per acre: $856 (Seed, Fertilizer, Chemicals, Machinery, Labor, Irrigation, insurance, etc.)

Average acres: 700

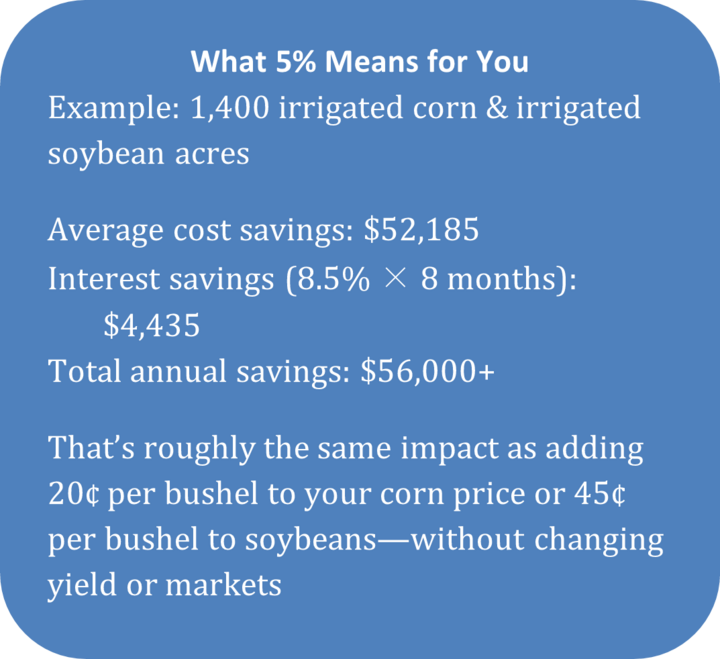

5% reduction = $42.80 per acre × 700 acres = $29,960 saved on corn alone.

Irrigated Soybeans (2024 NFBI Average)

Direct expenses per acre: ≈ $635

Average acres: 700

5% reduction = $31.75 per acre × 700 acres = $22,225 saved on soybeans.

Together, that’s $52,185 less operating expense—cash that stays in your account instead of revolving through the operating note.

The Ripple Effect on Your Operating Note

In 2024, the average farm paid $79,100 in total interest, up more than $15,000 from the year before. Every dollar you don’t borrow—or that you pay back sooner—reduces that expense directly.

Assuming an 8.5% interest rate for eight months:

$52,185 less borrowed saves approximately $4,435 in interest each year.

That’s a guaranteed return, risk-free. And the impact goes beyond interest—it improves liquidity. Reducing what you borrow by $55,000–$60,000 can strengthen your working capital ratio and financial safety net heading into 2026.

Where to Find 5%

From our work with efficient farms across Nebraska, we know that it’s rarely one big decision that makes a farm more profitable—it’s the small, disciplined choices in every category that add up. While there may be big wins in a few areas, most of the difference between an average and an efficient farm comes from watching the little things—the $1 or $5 per acre costs that quietly add up across hundreds or thousands of acres.

The first step is always to know your own costs. Averages, your neighbor’s numbers, or what your dad spent years ago, aren’t a substitute for knowing what you’re actually spending today. Once you have that, you can make smart, confident adjustments that fit your operation.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- Seed: Review hybrid and variety performance carefully. Make sure traits and technology are returning value for your soils and management, not just filling a sales quota.

- Fertilizer: Small gains in timing, placement, and rate control add up. The best farms don’t necessarily use less fertilizer—they use it more efficiently.

- Machinery: Efficiency isn’t always about buying new. It’s about managing ownership and operating costs. Reducing one tillage pass, coordinating custom work, or sharing specialized equipment can quietly save $5–10 per acre.

- Chemicals: Review your program annually. Resistance management is essential, but overlapping chemistry or “just in case” passes eat into margins. Stick to what you need for your fields, not what’s bundled in a promotion.

- Interest: Treat interest as another input to manage. Selling inventory earlier, keeping a tighter handle on the operating note, or refinancing long-term loans at better terms can make a measurable difference in total expenses.

The most profitable farms we work with are intentional and consistent. They question every dollar—large or small—and make sure every recommendation serves their bottom line, not someone else’s commission structure. Small efficiencies, repeated year after year, are what build resilience and long-term success.

Putting It Together: Small Adjustments, Big Leverage

For a 1,400-acre operation (700 corn, 700 soybeans), that $52,185 reduction in operating expenses cuts three full percentage points off the statewide operating expense ratio and adds about $37 per acre in working capital. Those are the kinds of moves that protect liquidity and limit the reliance on short-term debt—both key for staying resilient in a high-interest environment.

Final Thoughts

A 5% trim across inputs doesn’t require cutting corners—it requires intention. The NFBI data show that seed, fertilizer, and machinery together make up almost half of the cost structure for irrigated corn and soybeans. Targeting those areas first can have a meaningful impact on your bottom line.

Small, consistent adjustments—like shaving $35–$40 per acre off inputs—can strengthen your liquidity, reduce your interest costs, and buy you flexibility for when the next challenge arrives. That’s how you turn cost control into cash flow.

Tina Barrett

Executive Director

Nebraska Farm Business, Inc.

tbarrett2@unl.edu

402-464-6324