Post COVID Workforce Development: A Grass-roots Community Approach

By Kristina Bayton, Samantha Guenther, Blayne Sharpe and Cheryl Burkhart-Kriesel*

Introduction

As the world slowly emerges from COVID-19 both the virus and the lingering effects on the economy will be in the spotlight. Staggering rates of unemployment and drops in business activity have been well documented (Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims, 2020). We can already see resources within our country being reallocated to both employers and employees at the federal, state and local level as a result of the economic indicators (Thompson, 2020).

The size and scope of this economic event is staggering. As the country ramps up support it may be unrealistic to imagine that all areas of the country will receive the same kind of assistance at the same time. Federal state and local governments will have their priorities. It is reasonable to assume that population centers will be a high priority for both financial and human resources assistance. In a crisis this becomes a necessary approach where the goal is to reach the maximum number of people in the shortest amount of time. But what happens to those groups or locations that are not included in the priorities, such as less populated rural areas or minority areas embedded within urban centers? What can they do on their own to move their economy forward?

In the recent past, workforce intermediaries were often available to provide assistance. These groups come in a variety of forms. Some prepare job seekers for labor market entry and advancement through targeted training (Ganzglass, Foster, & Newcomer, 2014; Lowe, Goldstein, & Donegan, 2011). Others establish close working relationships with employers, educational institutions, and workers in an effort to influence local hiring decisions (Fitzgerald, 2004; Osterman, 2007). These groups may still be available in the post-COVID environment but their capacity may be diminished. Rather than waiting for their assistance, a crucial question is, “What can a community accomplish now by themselves in the short-term that will lay the ground work to better leverage and increase the impact of potential future state and federal resources?”

This is where a community self-help approach may offer value as a way to get the process started as well as defining the community trajectory. Communities have the power to go beyond “what was” and design a future that “could be.” It may be the perfect time to create a new path with more options for skill development and ultimately business growth and diversity within the community.

From a community perspective, the idea may seem daunting. Where does one start? But a closer look at workforce development reveals three foundational components. The steps are distinct, locally driven and also purposefully interconnected. They include: 1) bring together key community partners to inventory current assets and opportunities, and develop a local workforce plan that incorporates realistic strategic actions; 2) integral to the plan, create and incorporate methods to expand career exploration and development that resonate with both the current local adult and future youth workforce participants; and once these are outlined, 3) leverage both public and private financial support to help activate the plan.

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to offer smaller and possibly overlooked communities, specifically minority and rural communities, some ideas to re-energize their business economy and corresponding workforce in a way that opens up future opportunities in a post-COVID-19 world. The grassroots or bottom up foundational three step approach can be drafted immediately - it is a pathway designed by the community for the community. Having a plan of action that emerges from local aspirations and assets creates a roadmap for a desired future, given new opportunities and possible constraints post COVID. As resources become more available at the federal, state, and local level, the community will be ready to take advantage of those resources to strengthen their plan and move forward with their actions at a more accelerated rate.

These ideas are the culmination of a final project developed by three graduate students enrolled in a workforce development online course at the University of Nebraska. The timing of the course, late spring 2020, overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic. Merging the course content with the realities of the current economy generated discussions with a sense of urgency and purpose. The three components lifted up by the students as areas of interest were woven together to offer a basic three step, grassroots approach to workforce development. Although primarily designed for small rural or minority urban locations, the components and process are the workforce building blocks for a wide variety of situations.

The first component, bringing community partners together, offers the location a way to identify local assets and opportunities in a changing environment. Communities will need to have hard conversations on the types of actions that should to be undertaken in both the short and long term. Having the right partners around the table with a focus on both the immediate and the future will take keen group leadership skills as noted by the student author. Second, and fundamental to any workforce development plan, is a renewed look at career exploration and development. The student author of this segment chose to look at a specific workforce sector, sports, as a way to think about hidden and diverse employment opportunities that youth may not realize are available. There is more to sports than being a star in the NBA, NFL, MLB or NHL. Although the example highlights the sports sector, many employment areas fall victim to this same dilemma. We only think about jobs in the professions that we see. We cannot comprehend the support or back office employment opportunities that enable them. In addition, the author lifts up some of the barriers and obstacles that are present as they use sports as a pathway to career development. Third, and critically important, are ways to leverage both public and private community financial support to put a plan into action. Here the student author connected with a local workforce success story and investigated how the funding streams came together and included both the reasoning behind the support and the process and players that were needed to make it happen.

1. Bring Community Partners Together: Identify Workforce Assets and Opportunities

In a time of unprecedented change, many communities have had to adapt and implement a variety of actions, while facing social and financial hardships. Now, more than ever, communities are being asked to realign their resources as they work together to positively position themselves for the future. As communities focus on their economy, one of the central issues is the workforce – what is currently available in the short-term and what is needed in the future. To begin this conversation, it is important to bring community partners together to first identify workforce assets and opportunities.

A Foundation for Growth

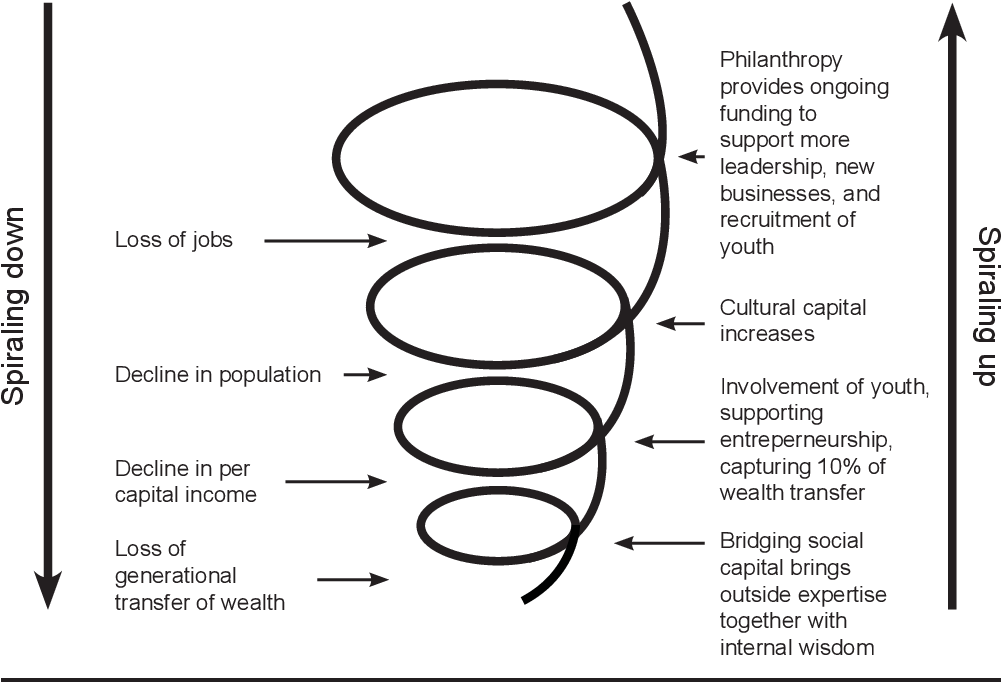

One resource, the Community Capitals Framework (Flora, Flora & Fey, 2004) can help community partners strategically identify community assets or capitals as a starting point for the conversation and as a model for growth. The spiraling up growth framework is a process where the investment of one community capital leads to the investment of other community capitals (Guiterrez, 2005) which ultimately builds upon itself to create a thriving community. But not all capitals are created equal. In a study by Emery and Flora in 2006, they contended that social capital, defined as the connection among people and organizations, is the entry point to the spiraling-up process (pictured below) and their results proved that when communities invest their assets in social capital across the community, it led to increases in investment of other capitals, leading to a spiraling up process for the community as a whole (Emery & Flora, 2006, p. 22).

However, this process cannot happen until individuals, businesses, and social and government entities can align their actions toward the present opportunities and challenges (Hagel, Schwartz, & Bersin, 2017). Therefore, it is crucial for local and regional development resources, educational and industry leaders, businesses, government agencies, and community members of all demographics to collaborate and determine future direction.

Ideally, the collaboration among the community representatives and the strengthening of social capital, will result in the development of a competency model which will identify key expectations for the members of the group According to London (2019), competency models are methods that organizations have adopted to communicate characteristics that the organization expects of its leaders. The development of a competency model includes identifying, defining, and measuring characteristics that are associated with successful performance (London, Smither, & Diamante, 2007). The advantages of competency models include clarifying what skills and abilities are important in the organization (London et al., 2007). On the contrary, a disadvantage of competency models is that they may highlight some characteristics while ignoring others. This prioritization of characteristics can result in unbalanced assessments/appraisals of organizational members and create an out casting of individuals with non-highlighted characteristics because they are not congruent with the group’s leadership model. Additionally, competency models may not represent the wide range of individual needs that may be important for success (London et al., 2007). Therefore, it is crucial to include a variety of individuals and representatives of the community to be present when drafting the plan.

Starting the Conversation

While there are provisions for individuals to spend more time at home and less time in public to decrease the spread of the COVID-19 virus, the ability to bring people together to share ideas through effective communication is still available. There are ample opportunities to connect via phone, cell phone, email, Zoom video-conferencing, Google Meetings, or even social media (Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram). Therefore, community leaders can identify key stakeholders and industry leaders, and reach out to start the conversation as community issues cannot be solved by individuals and organizations working independently (Hatch, Burkhart-Kriesel, & Sherin, 2018). By simply starting the conversation and sharing an idea, innovation, or a similar experience, community members may find comfort in knowing they are not alone and can support each other if they work together.

When those key leaders have been identified and come together to determine their plan, an important underlying consideration it that change can be difficult in a normal situation, and may possibly be more difficult in these uncertain times. Individuals accept and adopt change at different rates based on the perceived attributes of the change (Rogers, 2003), so it will be critical to ensure that the ideas moving forward are inclusive and relevant in order to engage others and lead to a spiraling up process.

One way to ensure that new efforts will be invested in by others in the community is to incorporate a more detailed discussion organized around the Community Capitals Framework that is linked to the local context. The Community Capital Framework can assist leaders to see a holistic view of the entire community, based on its assets. Also, as leaders strive to make changes, it will help them anticipate the project’s impact on the entire community.

To better understand this framework, the Community Capitals Framework offers a systematic process to view and analyze community change by outlining the areas of assets or capitals within the community including natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial, and built capitals. Natural capital includes the assets that abide in the natural environment of the location. For example, this could include parks, rivers and streams. Cultural capital is the way people know the world and live in it. Cultural assets might include ethnic festivals, a strong work ethic, or the willingness to join together to face a challenge. Financial capital refers to the financial resources available to invest in the community. This could include local and state banks or charitable organizations. Built capital is the infrastructure that supports the community such as main street buildings and roads. Political capital refers to access to power organizations and powerbrokers. This could include local and regional governments. Human capital is all of the skills and abilities of people in the community, and their knowledge. Social capital is the connections among people and organizations. For example, local clubs and groups would be considered social capital in the community. Social capital can also be differentiated between local bonding capital that brings people together and bridging capital that reaches out and extends to networks and organizations outside of one’s close circle. All of these capitals would be seen as assets or resources for community discussions focused on workforce issues.

Aspects of the Process

Community leaders can use this framework to guide their conversation, most likely with the use of a facilitator. The community group can start by identifying their ideal situation in a year, five years, and ten years. Individuals should be forced to think outside of the box as to the best ways their community can move forward after COVID-19, as well as considering future developments. Then, the community group can work through the community capital framework to determine the assets that they already have present in their community. Next, the community group should identify how the community can utilize their assets to create their ideal situation. These steps should be specific such as defining goals, actions steps, who is responsible, resources needed and deadlines. This can be supported by the creation of a competency model, so that moving forward, individuals and organizations will know what they need to do in order to fulfill both group and larger community expectations.

Ultimately, a key aspect to this process is being inclusive within the planning process – not only to a broad spectrum of demographics, but also within the brainstorming and planning process. People are inclined to invest in work that is important and meaningful to them, which strengthens social capital, a foundational step allowing a community to spiral up toward growth.

There are several opportunities that can arise out of the new situation the COVID-19 has presented. It is vital that community members take initiative and act on creativity and innovation that can create lasting effects in the local and regional workforce. For example, built relationships among new individuals may spark new collaborations to build upon human, cultural, or financial capital leading to the community spiraling up and seeing improvement in several community capitals. Whether that is taking the time to build internship programs among the local businesses and school or organizing an investment strategy for a desired improvement in the community, the possibilities are endless even in this new work environment. It just takes having the right people around the table willing to do the hard work of looking at their community assets in a new way.

2. Sports as an Industry: Opportunities and Obstacles in Building Career Skills

Background

Sports is an important aspect of our quality of life, regardless of whether you are a participant or spectator. But there is another benefit to this activity. For young adults, sports is a vehicle to develop soft skills including valuable personality and character skills that are translatable to the workforce. Particularly for minority students, getting involved in sporting activities is an avenue for them to improve their social status, overall health, and socioeconomic status. There is a correlation between minority youth and after school programs that suggests it will “decrease delinquency and serve as a buffer from negative effects of low socioeconomic status, discrimination, and neighborhood crime” (Stodolska, Sharaiveska, Tainsky, & Ryan, 2014 p. 63). Children's desire to participate in sports stem from their need to make friends, have fun, and to fit in socially. Parents desire for their children to take up sports is connected to the positive social, psychological, physical, and even financial benefits of participation. Children who are involved in organized sports perform better academically, have high interpersonal skills, and are more team oriented (Ghildiyal, 2015). While these skills are in high demand, there is a disconnect among athletes developing soft skills and general workforce employability skills.

According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 2018, there were 7, 3000,000 high school student athletes and on average 2% of them received college athletic scholarships (Gallup-Purdue, 2018). According to Malcom Gladwell, it takes 10,000 hours to become an expert and college coaches are looking for those who have put the hours in when recruiting this population (2008). While student athletes are in college they focus primarily on developing their athletics abilities. It is not uncommon for them to devote over 20 hours a week to their sport which is the equivalent of working a part time job. While there are resources provided to help them, they often do not have adequate time to take full advantage of them because they are juggling the pressure of performance and completing their degree. Statistics show that of the 492,000 athletes playing in the NCAA only 2% of them will go on to play professionally. Most of them will enter the workforce upon graduating (Gallup-Purdue, 2018). Transitioning from a student athlete to a member of the workforce is seldom an easy task. When student athletes graduate, the resources that were once readily available to them are removed leaving them feeling lost. Impacting this even further, many student athletes have vocalized they have no work experience to put on their resume and therefore do not possess marketable workforce skills or are knowledge about potential career opportunities. This could be a classic example of a workforce skills gap. A ready pool of potential employees with experience in teamwork, communication and possessing strong work ethics developed as a student athlete, being overlooked because their student experience did not allow for opportunities to create relevant and diversified career building experiences. To compound this situation, employers profess that they are trying to develop a culturally diverse workforce yet seem to bypass this pool of potential employees or student athletes which often represent minority populations. From the student perspective, it makes no sense and reinforces the notion that they are being “used” by the institution with little or no intent to provide the student with a successful career after college.

But this situation does not have to be the norm. According to Marri & Schramm, “employers, policymakers, educational institutions, students, and workers must collaborate effectively for workforce readiness initiatives to succeed” (2018, p.13). Educational institutions are considered “learning hubs for the future workforce” and can also “be a valuable workforce partner for employers seeking to develop critical and in-demand skills” (Marri & Reyes, 2018, p. 32). According to the Federal Reserve, high school is where students should receive information about technical and post-secondary career opportunities however research shows that over 30% of adults never received such information (2017). Of those who did receive the information, they did not receive it from professionals in those fields but rather from teachers and counselors who may or may not be up-to-date on details within specialized career paths. Even when the institutions are in place, there can be holes for youth in the career building process.

So how can this situation be turned around? What can be done at the collegiate level to compensate those who never received exposure to a variety of career opportunities or have the chance to build job skills? One approach could be a type of job rotation or job shadowing experience which could include two components. The first would be focused internally or “in house” while the second would look for external mentoring sources. Both opportunities could offer a job rotation program where students could shadow and learn about potential career opportunities available upon graduating. This experience would expose them to realistic work projects, necessary employability skills, and social networks that could be beneficial in their career development.

There are some tangible benefits. At the bare minimum, this program would help future job seekers rule out professions they do not want to pursue. A Gallup Survey constructed by the NCAA indicated that, 58% of former college athletes were disengaged at work (2018). According to Marri & Schramm, “workforce readiness data from employers in specific industries can shape education and training programs to ensure students learn the necessary skills to fill high-demand jobs (2018, p. 13).

Turning Obstacles into Potential Opportunities

There are many structural obstacles and assets for student athletes wanting to expand their career opportunities within and outside of the sports environment. Some of the most obvious are the NCAA, the urban economic environment, the college alumni support system, and employers themselves. A closer look into these structures helps to identify current opportunities and possible future structural modifications for job rotations and shadowing to occur.

NCAA - When working with student athletes, it is crucial that they maintain their amateur status. Therefore, it is very important to monitor this population so that they are not receiving any monetary incentives or gifts in return for their services. Also, it is important to document the number of Countable Athletically Related Activities (CARA) hours, which cannot exceed 20 hours. Countable activity hours include practice, meetings, and community relations opportunities (NCAA, 2020). This rule only applies to teams and not university mandated programs. Those involved in collegiate sports realize that there are three ways around this NCAA bylaw. The first is to designate a program as based solely on a student athlete’s volunteer participation on a team scale. This method consumes the most administrative time because it requires that the institution demonstrate the value of the program to every coaching staff member in order to gain approval. Another way to implement a job rotation program on a moderate scale is to gain the approval of university presidents and athletic directors. They then could provide this opportunity to their entire athletic department. If going this route, some features of the program would be required, which could consist of a presentation about the program and its benefits. But the actual participation in the job rotation and mentorship program would still solely be up to the student athlete. Another alternative would be to pitch the concept to the NCAA Commission Board and have them implement the program. They have the judicial power to require a baseline level of participation or implementation across all three divisions.

Urban Context - Involvement in sports comes with a hefty price tag as participants have to pay for uniforms, equipment, league fees, private lessons, travel fees, and summer camps. This financial burden can predetermine what sport an adolescent can play and can have lasting effects on the financial stability of a family. Some families sacrifice savings, family vacations, and other luxuries as they hope that one day hope they will receive a return on investment (Merkel, 2013). Urban families experience additional expenses as they may have to travel in order to participate due to the absence of neighborhood fields and recreation centers. Due to lack of government funding, these facilities are not well maintained which leads to outdated and unsafe environments. “A decrease in governmental funding for youth after-school programs has limited accessibility and feasibility for sports participation in lower socioeconomic areas. Dwindling financial resources also contribute to attrition in sports” (Merkel, 2013).

Alumni & Community Support - A Strada-Gallup Alumni Survey conducted in 2018, surveyed over 5,000 United States college graduates and asked them if their schools’ alumni network was beneficial during undergraduate school. Of those surveyed, 9 % disclosed the alumni network was helpful, 69% indicated they were indifferent, and 22% said it was unhelpful (Auter & Marken, 2019).

It is not uncommon fort post-secondary alumni to have low rates of involvement and support with their institution. However, the effects of successful intercollegiate athletic programs can increase community and alumni support. According to Grimes & Chressanthis, “a cross-sectional study of 56 NCAA Division I schools… found that several measures of athletic success including, attendance, postseason play, and winning percentage, are significant determinants of monetary contributions to a school's athletics program” (1994, p. 28). While alumni and community support can be an asset while major sports programs are succeeding, they may also become an obstacle if a team is having a down year.

Introducing a job rotation or shadowing program within student athletics and leveraging alumni connections seems like a logical approach. Alumni who were student athletes themselves or who have developed a strong connection to the school would likely want to work with students and share their expertise and insights. One of the assets in using alumni is that you would have connections to a wide variety of career fields. But this does not happen overnight. It takes time and energy to actively grow and maintain a consistent degree of alumni community support for any kind of student career exploration effort.

Employers - Employers are aware of the skills gap and they too can play a role in reducing the gap. When they neglect to help young adults in their community explore career opportunities, the gap will widen, and employers will continue to face challenges in recruitment. “Any successful effort to reduce skills shortages requires employer engagement. Employers recognize that skills gaps in their existing workforce act as barriers to productivity and business growth. They know which job vacancies are hardest to fill and the skills most needed to succeed in specific jobs” (Marri & Reyes 2018, p.18). When companies invest in the talent pipeline their investment not only improves the lives of the worker but also the company and the local community.

Employers do incur costs with workforce development. When implementing a pre-existing program or developing a new program, there will be human capital, opportunity cost, and financial (fixed and variable) costs (Nicholson et al., 2018). When companies are considering whether to invest in a skill development program, they must compare the cost of it to other recruitment and hiring methods (Nicholson et al., 2018). An overview of the employer costs is listed below in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Potential Costs Associated with Workforce Development Program

Fixed Cost |

Variable Costs |

|

Curriculum Development |

Employee Wages Supplies & Materials Time spent mentoring |

Adapted from: (Nicholson et al., 2018).

These costs can be offset by the reduction in employee turnover, direct supervision, errors, lack of productivity, and the on-board process of new employees. Besides investing in the workforce, companies need to invest in themselves as well. As the workforce becomes more skilled, they will be seeking jobs with benefits. Therefore, job retention is a two-way street where employers need to provide employees with incentives while employees must have the necessary skills and education to succeed and earn such incentives (Marri & Reyes, 2018).

Workforce Development & the Future:

Reducing the workforce skills gap will help align job seekers skills and industry needs which is a win-win situation for all parties involved. Investing in skill development and knowledge requires a great deal of time and resources but it has been shown to be mutually beneficial for employees, employers, and the community (Marri & Reyes, 2018). Businesses that invest in workforce development have seen positive return on investment which correlates to a spike in talent retainment, job attractiveness, and employee wage gains (Marri & Reyes, 2018). “A research report by WCCP (2014) finds that cities’ retention of graduates is about 50 percent on average, and these cities face emigration of their college-educated workforce due to a variety of reasons, such as skills mismatch, job availability, and integration into the community” (Marri & Reyes 2018, p. 20). By providing skill development programs, workers gain socioeconomic mobility, local communities will become more appealing, and businesses productivity levels will increase due to the talent pipeline. By 2024, the U.S. Department of Labor estimates that roughly 25% of the population will be over the age of 55 years old so the creation of a talent pipeline is critical to our country’s future economic success. Businesses who invest in workforce development will have the advantage as new skilled workers will replace pre-existing workers looking to exit the workforce (Marri & Reyes, 2018). The new incoming wave of workers who have participated in skill development programs will become just as productive or even more productive than current workers, repeating the generational cycle of workforce development.

The student athlete situation was highlighted in this discussion but there is an abundance of preexisting programs available in a wide array of industry fields that provide workers with training and education opportunities. However, some of these programs lack participation due to either lack of knowledge, they are not applicable to their situation, or they encounter obstacles as was identified in the previous student athlete and sports industry discussion. This is an ongoing challenge within our economy. According to Marri, & Schramm, “many employers do not take full advantage of the resources available to them through local higher education institutions. Small and medium-sized organizations sometimes are not aware of available resources or believe that they do not have a large enough contingent of trainees to invest in building training curriculum” (2018, p.13). As the world becomes more globally connected so should “the local chamber of commerce, community-based organizations, nontraditional workforce training providers, local and state workforce development boards, and financial institutions” in order to enhance the United States business and educational competitive advantage” (Marri, A. & Reyes 2018, p. 31).

3. Financing Workforce Development Initiatives

According to the National Skills Coalition, formula funding to states for adult, dislocated worker, and youth programs have fallen steadily since 2000, from approximately $5.1 billion to $2.8 billion in 2017, providing assistance to approximately 450,000 of the 165 million individuals who would benefit from training (Prince, 2018, p. 12 -13). This steady decline in state funded investment paired with the decreased investment by companies in workforce development for disadvantaged workers places a heavy financial burden for workers to identify and pay for training. Many communities seek to bridge the gap in financial resources by leveraging philanthropic investment, but it is a challenge for rural communities to compete for limited resources. Research indicates that larger regional economies employ more workers and typically have a more robust nonprofit sector, both of which create opportunities for attracting and deploying workforce development grants (Wardrip & Zeeuw, 2018, p. 41).

Traditional industries, like manufacturing, are declining across the United States. With an inadequate number of employers to absorb the displaced workforce, rural communities feel the immediate effects of this trend. Limited financial resources to re-train workers prevents the attraction of new industries. Insufficient training options handicaps the ability for communities to equip workers with the necessary skills to seek employment in thriving sectors like healthcare or ICT. Many rural communities have weathered the decline and have maintained manufacturing industries but have specific demands to train incoming workers in modern practices. Expert Benjamin Kraft advocates for manufacturing training that provides students with fundamental skills that are relevant to career paths in manufacturing and beyond saying, “while the manufacturing industry will continue to have cyclical decline, the sector continues to add millions of jobs each year and much of the manufacturing workforce will soon retire, creating additional opportunities for younger adults.” (Kraft, 2018, p. 266).

Communities that focus on innovation and engage a variety of stakeholders are better positioned to navigate financial limitations to build effective workforce development initiatives. A strong workforce development framework “taps into multiple viewpoints and ways of thinking, leverages diverse skills and knowledge throughout the community, and accesses an array of resources” (Hatch, Burkhart-Kriesel, and Sherin, April 2018). Resiliency depends on strong leadership, collaboration, and the ability to pivot community-based assets to remain relevant to industry needs. Using the City of Fort Smith, Arkansas as a model, the following discussion will highlight the unique challenges and opportunities of engaging stakeholders across philanthropy, the private sector, and government to finance workforce development programming during periods of economic challenge.

Fort Smith, Arkansas: Innovating through Decline

Over the last ten years, Western Arkansas has lost thousands of traditional manufacturing jobs with the departure of large companies like Whirlpool (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 2012). These closures have pressured local government and educational leaders to work with the private sector to re-train sections of the existing workforce and to create training programs for those entering the workforce. In 2019, the Fort Smith Public School District (FSPS), the largest district in Western Arkansas, announced the launch of a new career technology center for high school students. The project was made possible by a $1.4 million federal grant, a donation of facilities by a family foundation, a voter approved millage increase, and a private grant from a locally headquartered global manufacturer (Fort Smith Schools, February 2019). The program will educate over 300 high school students per day in courses that are taught by professors from the University of Arkansas – Fort Smith (Southwest Time Record, February 2019).

In 2017, FSPS opened a dialogue with the community about the future of education in Fort Smith. In an interview with Dr. Udouj, the newly appointed Director of the Career and Technology Center, he explained that under the leadership of the FSPS superintendent, transparency and community input was prioritized in the community dialogue. During planning sessions, carefully selected community members were divided into working groups and a citizen’s council to participate in a process that led to the production of FSPS’s Vision 2023, a five-year strategic plan. In 2017, the Plan, which emphasized efforts to prepare students for high tech careers through the development of the Career and Technology Center, was approved by the Board of Education.

Public Investment

Dr. Udouj shared that engaging the community during the planning process was key in cultivating the needed financial support, especially as Fort Smith was in the midst of a national manufacturing downturn. If community advocates had not been created, a financial request in the form of tax revenue would have been a tough sell to the citizens of Fort Smith. Beyond community advocates, the FSPS also prioritized communications with local media outlets to ensure the Vision 2023 plan was clearly communicated to the public. Proponents for a proposed millage increase were able to reference the Plan and how the funding would be invested. Fort Smith Regional Chamber of Commerce President and CEO Tim Allen was one of the strongest advocates for the millage increase saying, “In Fort Smith we’re in the same situation the rest of the nation is, and that is we need more people and we need them to have more skill sets. I see the career center as being the pipeline” (Talk Business & Politics, 2019). The strategic communication worked and in 2018 voters approved the school millage increase, the first increase in 31 years. The millage investment is expected to raise over $120 million, which is a significant investment for a town that has faced significant un-employment challenges. The FSPS leadership feels a responsibility to continue to practice transparency to report returns on the community’s investment into the new workforce development initiative.

Local leaders and the FSPS coordinated efforts with Arkansas’ congressional leadership to solicit funding beyond local resources. In 2018, Fort Smith was awarded a $1.4 million federal grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration (EDA). This grant was a strategic effort by FSPS and local economic development officials. Dr. Doug Brubaker, the Fort Smith Public Schools Superintendent, celebrated the collaboration and federal investment saying “This state-of-the-art facility will connect students with opportunities in advanced manufacturing, healthcare, and information technology careers with a focus on engaging instruction in the science, technology, education, art, and math (STEAM) disciplines. This will lead to the retention and expansion of employment opportunities in our state. We are grateful to Senator Boozman, Senator Cotton Congressman Womack, Governor Hutchinson and our partners across the River Valley who continue to support this initiative. We look forward to seeing this important project take shape.” This federal investment represented an opportunity for local and national leaders to transition the conversation from Fort Smith’s well-known economic challenges to a public announcement celebrating innovation and resiliency.

Philanthropic Investment

Between 2008 and 2014, the largest foundations in the United States made 24,633 grants totaling roughly $2.6 billion to support workforce development activities (Wardrip & Zeeuw, 2018). Philanthropic investments in workforce development “permits the sorts of experimentation and piloting that other funding sources, particularly public ones, does not. Foundations are well positioned to provide first-in money, but the public sector might be better resourced to provide continuing financial support for proven solutions” (Wardrip & Zeeuw, 2018, p. 38). Philanthropic investment is great for start-up capital, but it can be challenging to get, especially in communities that lack the resources of their urban counterparts. A good approach for small urban areas or rural communities is to target local foundations that have direct knowledge. These organizations will be generally aware of the opportunities that workforce development initiatives can create for the community and may have less stringent application processes.

According to Dr. Udouj, FSPS was approached by the William L. Hutcheson Family, a local family foundation, with an offer to invest in the startup of the Career and Technology Center. Mr. Hutcheson, who died Feb. 18, 2017, opened a shoe-store chain that was eventually acquired by Walmart. Hutcheson joined Walmart as an executive and oversaw Walmart’s acquisitions in Canada. The FSPS Vision 2023 strategic plan resonated with the Hutcheson Family’s giving strategy and in 2019 the family generously gifted a 182,000 square foot building to serve as a site for the expansion of Career and Technology Center. The donation saved the district at least $3 million that had been budgeted to buy an existing building. Susan McFerran, Fort Smith School Board President welcomed the philanthropic investment saying, “This generous gift will enable generations of our kids to develop the ‘viable plan, applicable skill set and creativity’ called for in our Vision 2023 Strategic Plan” (Fort Smith Public Schools, February 2019).

Infrastructure costs are attractive to many foundations as they represent a legacy opportunity versus funding operational or administrative expenses which may require multi-year commitments. The investment from the Hutcheson Family has raised awareness within the Fort Smith regional philanthropic community and has provided start-up resources for the Career and Technology Center. FSPS is coordinating with the FSPS foundation team to coordinate requests from additional foundations and corporate partners. Dr. Udouj explained that FSPS has solicited the services of a marketing and branding agency to streamline their communication tools and messaging. These communication pieces will resonate well with a giving community that appreciates the combination of well-produced qualitative information, impact descriptions through storytelling, and results-driven quantitative measurements.

Private Sector Investment

The private sector’s views on workforce development have progressed over the last few decades. Traditionally, employers depended on well-funded public schools, trade organizations, and vocational colleges to create a talent pool of candidates. As technological advances demanded more skilled labor, educational institutions and organized support for workforce development were weakening. Research indicates that a decline in unionization and increased fragmentation of the labor market were accompanied by the dismantling of traditional vocational training mechanisms in local education systems. Moreover, large employers pushed cost-control measures down the supply chain, making it difficult for smaller employers to invest in skills training (Conway & Giloth, 2014a, p. 9).

Workforce development expert Stuart Andreason stresses the need for workforce development programs to keep stakeholders engaged by reporting strong returns on their investment. Andreason references that stakeholders and programs are a “patchwork” that requires strong coordination to connect the pieces. In his article, Coordinating Regional Workforce Development Resources, he explains “that as workforce development becomes increasingly critical to local economic development efforts, investing in ways to make the system able to be more easily navigated and understood by businesses is critical to positioning workforce development organizations as key partners in economic development efforts and business services.” (Andreason, April 2015)

Fort Smith’s economic development leaders did a great job in creating a strategic plan that the career academy’s private sector stakeholders deemed valuable. According to Dr. Udouj, FSPS leadership included the private sector in the Vision 2023 planning process and have maintained communication with industry leaders as the Career and Technology Center’s curriculum is established. Jason Green, vice president of human resources for ABB, a large manufacturer in Fort Smith, is a vocal proponent of the Career and Technology Center. He is also a key stakeholder whom Dr. Udouj consistently engages in strategic planning activities. Green publicly promoted the initiative and the need for private sector engagement when he said “We’ve always said a program like this needs state-of-the-art equipment and state-of-the-art facilities for our students to learn in. So to have a facility of this size, it will be that kind of place for many, many generations to come.” (Fort Smith Public Schools, 2018). Through Green, Dr. Udouj has leveraged ABB’s technical supervisors in assessments of learning outcomes and in the curriculum development process. The objective is to install equipment and technology similar to that used in ABB’s manufacturing processes and to create apprenticeship opportunities for students at ABB. These measures will ensure that the Career and Technology Center is building goodwill with ABB and producing a talent pool that the company will value. This will be a model that the Career and Technology Center can replicate with other area employers.

This value to ABB may translate into opportunities for Dr. Udouj and FSPS leadership to seek financial investment from ABB and other private sector partners. The precedent is already in place as ABB’s Westville, Oklahoma Motor Plant team recently presented a donation to another career academy, which allowed for the purchase of machine tooling and instrumentation for the organization’s industrial maintenance program. An ABB executive praised the partnership saying, "They have been more than willing to learn what is needed in the manufacturing community and have tailored their program to fit those needs. We are proud to be able to contribute to this organization, we look forward to continuing to partner with them in the future." (Baldor/ABB, September 2015)

The FSPS leadership may have an opportunity to solicit additional financial support from local community banks through Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) contributions. In July 2016, the Federal Reserve clarified that banks can get CRA credit for “creating or improving access by low- and moderate-income persons to jobs or to job training or workforce development programs” (Department of the Treasury 2016). This announcement encourages banks to engage in workforce development and specifies to bank examiners that workforce development can count as a CRA-creditworthy activity (Blum & Shepelwich, 2017, p. 17). By contributing to the Career and Technology Center, community banks are incentivized by CRA credit and the opportunity to build brand reputation within Fort Smith.

Fort Smith’s Career and Technology Center: An Exercise in Leadership

Fort Smith’s Career and Technology Center is a fascinating example of both community leadership and action. Both the FSPS and community leaders observed best practices when engaging community stakeholders on the creation of the Career and Technology Center. The officials were collaborative and ensured that local employers were seen as co-creators of the Center’s curriculum frameworks. FSPS prioritized transparency with the citizens of Fort Smith, which created understanding and overwhelming support which was represented through the passage of a millage increase. Leaders were strategic in their engagement with the non-profit community by identifying foundations that provided start-up support and created confidence for other philanthropic investors. These leaders continue to navigate a challenging economic situation in Fort Smith but approach their work with an understanding that it takes a “patchwork” of stakeholders to pivot community assets towards innovative workforce development solutions.

Moving Forward Post COVID

Communities have never been here before – no one knows exactly what economic recovery will look like in the months ahead. But we do have past workforce history, resources, observations and insights to draw upon as we position ourselves for the future. For this particular workforce project, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s, Investing in America’s Workforce, three book publication series (2018) provided key data and varying professional insights as a starting point. In addition, the students framed each component based on their past individual and community experiences. Blending outside resources with personal insights may be the norm as we formulate the best possible decisions in this shifting economic landscape.

The intent of this project was to create a basic grass-roots workforce process, especially for niche locations like smaller rural communities or urban neighborhoods, in a post-Covid environment. It is hoped that this process and unique economic timing sparks community workforce discussions that go beyond the present realities of “what was” to a future of increased business growth and diversity of ”what could be.”

References

Andreason, S., & Carpenter, A. (2015). Fragmentation in Workforce Development and Efforts to Coordinate Regional Workforce Development Systems: A Case Study of Challenges in Atlanta and Models for Regional Cooperation from across the Country (2015-04-01). FRB Atlanta Community and Economic Development Discussion Paper No. 2015-2. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3128153

Auter, Z., & Marken, S. (2019). Alumni networks less helpful than advertised. Gallup. https://bit.ly/34Qnwq5

Baldor/ABB. Press Release. (2015, September 15). https://www.baldor.com/our-profile/news/company-news/detail?id={2415E1C3-691A-4D15-87C3-3864F0B0D1AB}

Blum, E. S., & Shepelwich, S. (2017). Engaging Workforce Development: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations. https://www.dallasfed.org/-/media/Documents/cd/pubs/workforce.pdf

E., V. H. C. (2018). Investing in Americas workforce: improving outcomes for workers and employers. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Emery, M., & Flora, C. (2006). Spiraling-up: Mapping community transformation with community capitals framework. Journal of the Community Development Society, 37(1) p.19-35.

Federal Reserve. (2017, February 2). Experiences and perspectives of young workers. https://bit.ly/2z6Q0jE

Fitzgerald, J. (2004). Moving the workforce intermediary agenda forward. Economic Development Quarterly, 18, 3–9.

Flora, C., Flora, J. & Fey, S. (2004). Rural communities; Legacy and change. 2nd Ed. Boulder CO: Westview Press.

Fort Smith Public Schools. (2017). Vision 2023. https://www.fortsmithschools.org/domain/2828

Fort Smith Public Schools. (2019, February 25) Press Release. Building Donated to Support FSPS.

G. Udouj, personal communication, May 2020.

Gallup-Purdue Index Report (2018). Understanding life outcomes of former NCAA student-athletes. https://bit.ly/2KjqhHe

Ganzglass, E., Foster, M., & Newcomer, A. (2014). Innovation in community colleges. In M. Conway & R. Giloth (Eds.), Connecting people to work: Workforce intermediaries and sector strategies (pp. 301–324). New York, NY: Aspen Institute.

Ghilidiyal, R. (2015). Role of Sports in the development of an individual and role of psychology in sports. Mens Sana Monographs 13 (1), 165-170. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.153335

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Hachette Book Group.

Grimes, P.W. & Chressanthis, G.A (1994). Alumni contributions to academics: The role of intercollegiate sports and NCAA sanctions. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 55 (1), 27-40.

Gutierrez-Montes, Isabel. 2005. Healthy communities equals healthy ecosystems? Evolution (and breakdown) of a participatory ecological research project towards a community natural resource management process. San Miguel, Chimalapa (Mexico). PhD Dissertation, Iowa State University, Ames, IA.

Hagel, J., Schwartz, J., & Bersin, J. (2017). Navigating the future of work. Deloitte Rev, 21, 27-45.

Hammer sly, L. (2012, June 17). Whirlpool's 1,000 layoffs just tip of iceberg. Arkansas Democrat Gazette.

Hatch, C., Burkhart-Kriesel, C., & Sherin, K. (2018). Ramping Up Rural Workforce Development: An Extension-Centered Model. Journal of Extension, Volume 56 (2). ISSN 1077-5315. https://joe.org/joe/2018april/a1.php

Kraft, B. (2018). High School Manufacturing Education: A Path toward Regional Economic Development. Investing in America’s Workforce. https://www.investinwork.org/-/media/Files/volume-two/High%20School%20Manufacturing%20Education%20A%20Path%20toward%20Regional%20Economic%20Development.pdf?la=en

London, M. (2019). Leadership assessment can be better: Directions for Selection and Performance Management. 58–88. doi:10.4324/9781315163604-4

London, M., Smither, J., Diamante, T. (2007). Best practices in leadership assessment. The Practice of Leadership: Developing the next Generation of Leaders, 41-63.

Lowe, N., Goldstein, H., & Donegan, M. (2011). Patchwork intermediation: Regional challenges and opportunities for sector-based workforce development. Economic Development Quarterly, 25(2), 158–171.

Marri, A. & Reyes, E. (2018). Turning the skills gap into an opportunity for collaboration. In S. Andreason, T. Greene, H. Prince, & C.E. Van Horn (Eds.), Investing in America’s Workforce: Improving Outcomes for Workers and Employers (pp. 17-32).

Marri, A. & Schramm, J. (2018). Leveraging evidence based and practical strategies to reduce skills gaps. In S. Andreason, T. Greene, H. Prince, & C.E. Van Horn (Eds.), Investing in America’s Workforce: Improving Outcomes for Workers and Employers (pp. 11-15).

National Collegiate Athletic Association (2020). Countable athletically related activities. https://bit.ly/2zeKVGd

Nicholson, J., Noonan, R., Helper, S., Langdon, D. (2018). Apprenticeship benefits and costs. In S. Andreason, T. Greene, H. Prince, & C.E. Van Horn (Eds.), Investing in America’s Workforce: Improving Outcomes for Workers and Employers (pp. 51-66).

Osterman, P. (2007). Employment and training policies: New directions for less skilled adults. In H. J. Holzer & D. Nightingale Smithy (Eds.), Reshaping the American workforce in a changing economy (pp. 119–154). Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Prince, H. (2018). Rebalancing the Risk: Innovation in Funding Human Capital Development. Investing in America’s Workforce. Retrieved from https://www.investinwork.org/-/media/Files/volume-three/Rebalancing%20the%20Risk%20Innovation%20in%20Funding%20Human%20Capital%20Development.pdf?la=en

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusions of innovations. New York: Free Press.

Stodolska, M., Sharaievska, I., Tainsky, S., & Ryan, A. (2014). Minority youth participation in an organized sport program: Needs, motivations, and facilitators. Journal of Leisure Research, 46 (5), 612-634.

Thompson, E. (2020). Nebraska Monthly Economic Indicators April 29, 2020. UNL College of Business – Bureau of Business Research. https://business.unl.edu/outreach/bureau-of-business-research/documents/LEI_4_2020.pdf

Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Data Report r539cy. (2020). U.S. Department of Labor – Employment and Training Administration. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/wkclaims/report.asp

Wardrip, K., Lambe, W., & Zeeuw, M. d. (2016). Following the Money: An Analysis of Foundation Grantmaking for Community and Economic Development. The Foundation Review, 8(3).https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1313

Watson-Fisher, J. (2019, October 1). Fort Smith School District Awarded 14-million Federal Grant for Career-tech Center. Southwest Times Record.

* K. Bayton, S. Guenther and B. Sharpe were graduate students enrolled in the University of Nebraska – Lincoln CDEV 827 online community workforce development course during the spring 2020. Dr. C. Burkhart-Kriesel, Extension Specialist in Community Vitality and Professor in Agricultural Economics, was both the instructor and collaborator on the final project.